By JAMES BROOKE

Facing final exam pressures common to all boarding schools, students here have found an uncommon way to unwind. Following the bouncing ponytail of Al Blackhorse, their history teacher, Indian students hop, skip and dip in a clockwise whirl of the Navajo grass dance.

It's spiritual, social and a stress reliever," Mr. Blackhorse said after the taped chants and drumbeats of the late afternoon powwow faded from the brand new campus of the Native American Preparatory School.

For decades, the words "Indian boarding school" could conjure up fearful, Dickensian images: cold showers barracks where white teachers cut Indian boys' braids, burned their traditional clothing, handed out English names and forbade them from speaking the language of their parents.

Richard Pratt, founder of the first Federal Indian boarding school, set the tone in 1892 when he lectured a congress of educators: "Kill the Indian in him and save the man."

One century later, on a 1,600-acre campus dotted with pinon pines and cut by the Pecos River, a group of white and Indian educators are starting what they hope will become a model for a different kind of Indian boarding school education for America's next century.

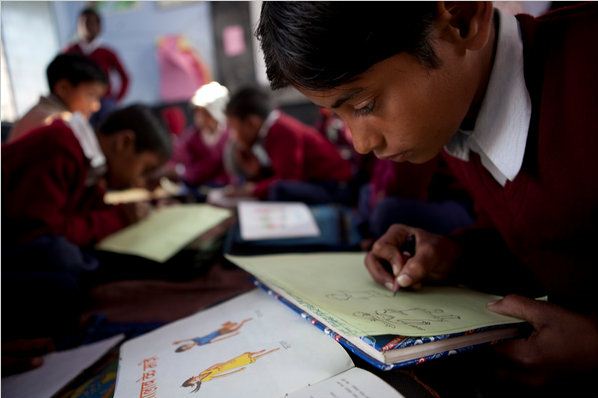

After seven years as a summer school, the Preparatory School moved in August into its new, $6 million campus here in high mountains 40 miles east of Santa Fe. In this setting, the school offers a rigorous, traditional curriculum coupled with studies of Indian literature, art and history, as well as weekly visits by Indian leaders, artists and professionals.

The idea is to offer bright Indian high school students the kind of elite education that privileged white children have long enjoyed at New England boarding schools. But instead of paying an annual tuition valued at $16,000, Indian families pay only $900.

"We want to fill the American Indians' educational hole -- doctors, scientists, educators, business leaders," said Richard Prentice Ettinger, the chairman of the school's board. The son of a founder of the Prentice Hall publishing house, Mr. Ettinger has made the family foundation, the Educational Foundation of America, the school's principal financial backer. With an annual budget of $1.7 million, the school is almost entirely privately financed.

The need for improved Indian education is clear. Scoring at the bottom of America's five major racial groups, only half of Indian students graduate from high school and only 3 percent graduate from college.

At the same time, Congress shows little interest in increasing Federal investment in Indian education. In its most recent version of the Federal budget, Congress calls for a 10 percent cut for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, an agency that maintains 187 schools.

Closer to home, Congress this year cut in half, to $5 million, the budget for Santa Fe's Institute of American Indian Arts, the nation's only arts college for Indians. With Congress debating an end to Federal financing altogether next year, the Institute's President, Perry Horse, resigned on Nov. 21.

Here, on rolling hills of the western Plains where Pecos Indians once hunted buffalo, the Native American Preparatory School may be forging a formula for improved educational results. A followup study of 50 students from the 1988 summer session found that five years later three-quarters were enrolled in college.

The school not only combats the low expectations that traditionally handicap teachers of Indians, but it also combats the low self-esteem that traditionally handicaps Indian students. In Mr. Reyna's art class, students work on baskets and masks under a wallboard that proclaims: "I am talented, skillful and intelligent! I look, act, think and dress like a winner!"

For some Indian teen-agers, accustomed to undemanding reservation schools, the educational atmosphere here is too hot.

In early September, only a few days after the first freshman class of 50 students arrived, a mini-riot erupted on campus, leaving a trail of broken lights and wounded feelings.

"Everything around here says you are in a resort, then you get nailed with homework," Norman E. Carey, the head of the school, said as he strolled the grounds on a recent afternoon. "Some of the students never had homework before. A great deal of anxiety contributed to the flare-up."

The school closed for 10 days as a result of the disturbance. When it reopened, two teachers and eight students did not return.

But, as the school nears the end of its first term, many of the 40 students expressed enthusiasm in interviews.

"Time goes by so fast here -- one day you think it's Thursday and it's already Saturday," said Nikki Nez, a 14-year-old who wore a Navajo-style choker, fashioned from bone, brass beads and artificial sinew.

"Back in Santa Fe, I felt like I wasn't working hard -- and I was getting A's and B's," she continued. "This is a big change, from easy to real hard."

The daughter of a woodworker who dropped out of high school, Nikki said she was "hoping to go to Stanford or Berkeley."

Teachers here say they work to draw Indian children out of their traditional classroom reticence that stems from the students either viewing the teacher as an elder, worthy of rapt attention or being intimidated by non-Indians in the class.

Fred Leon, a 14-year-old from Laguna Pueblo, discussed his new assertiveness in an interview a few minutes after he addressed the student body about his fall-term art projects.

"At home, I was mixed with Anglos and Mexicans -- the others dominated the class, and I felt left out," he recounted. "Here, it's Native Americans. You get attention, you get called on."

After three months, Fred, the son of a small rancher, said he was still in awe of the school's creature comforts. "There's only two to a room," he said, "and you get a big old bed all to yourself."

With plans to steadily expand until it has a traditional four-year student body, the school is starting a $20 million capital drive to raise money to build additional housing for faculty and students, a library, a gymnasium and a science laboratory.

Although only a tiny fraction of Indian students will ever have the opportunity to attend a school like this, school officials believe they can set a model for Indian education and provide role models for tribal populations. Already, this drop in the bucket is making some local splashes.

"At home on the reservation, there is only TV and drunks," said Denisa Livingston, a 14-year-old from Shiprock, Ariz. "When I go home now, people look at me as a model."

And for students who want to know how the old Indian boarding schools were, they need only to ask Mr. Blackhorse, a 33-year-old veteran of the war in the Persian Gulf.

"Everything was very regimented -- you marched around campus, there were bunk beds, open bay showers all together," the teacher recalled of his New Mexico boarding school of 25 years ago. "Everything stressed the assimilation process. I was always getting intimidated by the Anglo teachers. I didn't want to ask questions in class."

Here, school directors encourage close family ties. Students can go home every other weekend. Telephones in their rooms can receive incoming calls. Parents can work off their tuition bills by spending weekends as dorm monitors.

The other evening, after students had drifted out of the cafeteria after dinner, Mr. Blackhorse recalled how old-style Indian boarding schools used to handle the family unit.

"I remember my grandparents dropping me off at the school, when I was 4 years old," he recounted. "I remember seeing their old car going down the road and running for the door. The older boys stopped me."

Source: NYTimes